Free shipping in Ireland over €25. Free worldwide shipping on orders over €50

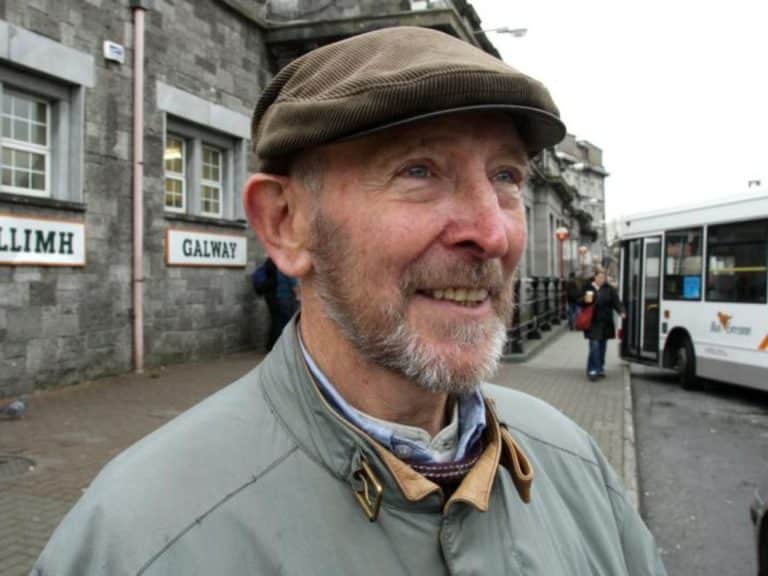

GERRY GALVIN was born in Limerick in 1942 but later moved to Oughterard, Co. Galway. He was a chef and former restaurateur, author of two cookbooks, The Drimcong Food Affair (McDonald Publishing, 1992) and Everyday Gourmet (The O’Brien Press, 1997), and was a columnist for Organic Matters magazine. His poetry and short stories have been published in newspapers and magazines in both the U.K. and Ireland. Sadly, Gerry passed away in 2013.

Here are the living and the dead, and their occasions. Here is the earth, travelled, considered and understood. Here are the marks a man makes, measuring his time in the world, the joy he has had of it, the wisdom gained. Here are poems ‘loud with knowing/and unknowing’, articulate speech from a clear mind, a warm and accepting heart.

— Theo Dorgan

James dined regularly at Le Gourmet. It was not his favourite restaurant in London, not at all, nor did he expect to be surprised by Bruno’s plats du jour. He knew them all: Fried Fillets of Sole in Almond Butter every Tuesday for years, Osso Bucco on Wednesdays, Navarin of Lamb Thursdays, Bruno’s Bouillabaisse Fridays, et cetera, et cetera. Happenstance? Hardly. He dined there because of its convenience; his house was just a block away. Whatever about the food, the music was regrettable, wall-to-wall Piaf.

Maître d’ Bernard greeted him. “Your special table, Mr G.” Rarely was he addressed as he saw fit, James Livingstone Gall, for most a mouthful too far. “Mr G” was his moniker among restaurateurs, its snappy familiarity a token of distrust under the pretence of mutually beneficent exchange. Fact was they hated his guts.When it boiled down to it, he was a critic and the conventional assumption was that he had the power to destroy reputations as easily as he might gild the lily. They feared him and fawned. Butter was their stock-in-trade and Bernard spread it well.

James ordered the sole with a side dish of spinach and a bottle of Chenin Blanc from the Loire, serious and redolent of new mown hay. He had a keen nose. Lone dinners did that for a man. Solitariness he saw as a catalyst of understanding and assimilation in matters of the arts and music. Bernard was waspish as ever, breathing sweet poisons in his ear. He burnished James’ ego with gossip about rivals and their restaurants.

“You hear about Carlo?”

“Carlo Morelli?”

“His wife and the sous chef.” Bernard made a play with hands and fingers to demonstrate an adulterous act.

“Not at all surprising, Bernard. The lady merely makes up for lost time. Carlo’s been laying waste to waitresses for years.”

“But he’s a man!”

James swallowed more wine, suddenly recalling the childhood taste of his mother’s skin after an Atlantic swim. So, so cold. The memory made him tremble and he consciously pushed it away, scanning the room for interesting faces. As the night’s custom peaked, kitchen clatter and called orders mingled in a rising clamour. To James the noise from a well-run kitchen was not noise, it was music composed and orchestrated by the chef. At best it brought to mind Strauss, one of the younger’s frantic polkas.

Parties of businessmen shared lubricated opinions, couples sought hands across tables in flickering light. He was the only lone diner, drawing glances that showed interest and then slipped away. Like it or not his was a formidable presence, not your caricature, corpulent, sage-gone-to-seed food critic, not in any shape or form. He was, he would have us know, the handsome exception, his early middle-age in charge of itself; he had his hair and his height, six foot at a stretch; when he opened his mouth, heads turned; submitted to the surgery of his pen, they rolled.

A waiter went by carrying a tray of food aloft: oysters in the half shell, a bowl of soup and a still tumescent soufflé. His identification clock clicked on: oysters, the flat Galway Bay variety; soup, tang of

curry, coconut, coriander; the soufflé, ego food, puffed-up and erect

with goat’s cheese, egg, flour and butter. It paid to be right. He believed he had that quality, rare among men, of picking up the most ephemeral scents. It was essentially an animal phenomenon: bulls drawn aggressively to the inviting odours of cows; cats and dogs, however tamed, connecting to coded smells of genitalia in heat; a sexually-aroused human giving off smells of the sea not unlike that of crustaceans and fish. Ruminating as he drank, his eye was drawn to the couple just arrived at a table for two, Bernard seating them, male facing him.

“No!” The woman was emphatic. “You know I like my back to the kitchen.”

As they changed places she looked across the room, straight at James, lingered for a moment too long while an outstretched hand accepted the proffered menu. His look lingered too. Whatever he saw there focused him with an involuntary jolt. Ever on the qui vive, he sensed he was on to something. He looked up again and at that precise point she did also. Bernard reappeared with what he believed to be a flourish, blocking James’ view.

“Rognons sauté, sauce Madère,” the lady said. “And a glass of Malmsey on the side.”

“And after the kidneys, madame?”

“It’s not listed, but I’ll have osso bucco.”

Bernard stiffened, head inclined. “Apologies madame, osso bucco is Wednesday, may I suggest tonight’s—”

“Osso bucco!”

Bernard, contrite, turned his attention to her friend. “And Mon-sieur Felix?”

Her interjection brooked no indecision. “La même chose!”

Bernard scuttled to the kitchen, the lady’s certainty snapping at his heels.

Her companion, a man of James’ age, buttered a bread roll and sipped Madeira wine with sly, practised ease. James signalled for another Port. “Not ‘87. Is there a decent Cockburns in the house?” The quiver besieging his lower lip modified to an imperceptible tic under the influence of an imperious Cockburns ‘55.

Alzheimer’s

This is not childhood revisited.

Quizzes twist your face into a blob,

the density of dough, tight, intense;

eyes whirlpool and attune to nonsense.

I look at you and feel you ferment

gibberish in all directions; then

as you tumbril down the avenue,

in practised unison we wave.

Goodbye, today, is almost all we have.

Your head is an old people’s home,

demolition crew is in.

Windows shatter, doors agape,

collapsing walls disturb old dust,

make room for Babel’s bedside chat,

telling memory a thing or two.

Unravelled tapes make music still;

you disintegrate to Mozart,

Liszt. Over and over again,

your favourite pieces scatter.

All matters now are love’s remains.

You have gone

to wherever you are, leaving a body

in the bed, thin limbs

scaffolding remnants.

Slack mouth sucks long drafts, fuel for

descents that stay a long time down.

We gather round, an audience

to your long-running one-woman show

winding slowly down.

Silently we urge you on: ‘Sing,

sing again for us. Sing

another verse of your swansong.’

December in Drimcong

In the damp wood

composting leaves

soften the tread of all:

dogs, walkers, sheep,

the night stalkers,

badger and fox.

The fox shits and slinks astride a shadow;

the badger bustles—

a giant piebald beetle

working the earth.

After dawn, down by the lake,

a heron, water-lapped, startled

by the night echo on a wind,

takes off on a slow narrative glide

to the copse of hazels guarding a pool.

The heron, sensing unwelcome

from thicket and hazel height,

lands. Water whispers.

Eels wriggle out of sight.

Pikes’ backwash

alerts rudd, perch, bream.

Vagrant fish diverge into shallows.

The heron waits.

ISBN: 978-1-907682-07-0 | Pages: 240 | Published: 2011

Killer à la Carte introduces us to James Livingstone Gall, a respected restaurant critic, creative chef and serial killer, matched in evil by Claudia Catalano, heiress to an hotel empire. We wine and dine with them and watch as they kill with ease and impunity. This book from Gerry Galvin, first class chef, restaurateur and poet, is one long captivating prose poem.

ISBN: 978-1-907682-00-1 | Pages: 64 | Published: 2010

We travel with a keenly observant man, and one of many moods; we glimpse his loves — of family, of nature and of the changing seasons, for example – share reflections on experiences in a year spent travelling in a camper van, feel his personal longings and losses, and the relentless passage of time (review by Georgina Campbell, Ireland Guide).